A story, stories.

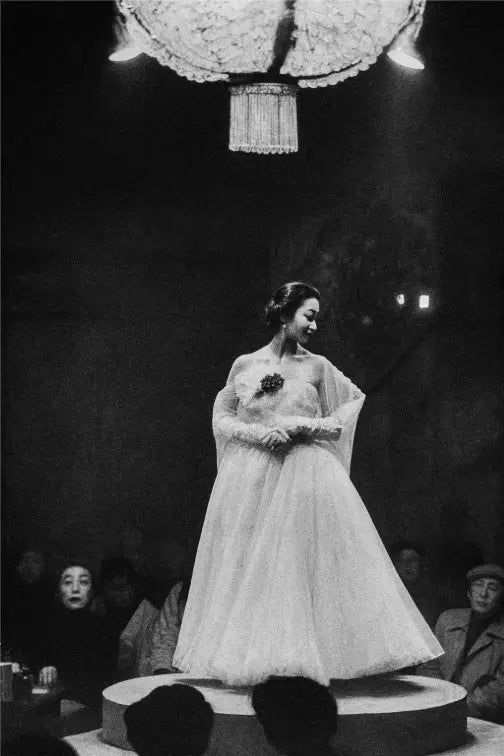

Christian Dior at Bunka, 1953 — The Paris–Tokyo Bridge

In 1953, Christian Dior was at the height of his fame. Since his famous "New Look" of 1947, his silhouettes with cinched waists and full skirts had restored an image of luxury and elegance to post-war Europe. But the couturier wasn't limiting himself to the West: he dreamed of opening Parisian haute couture to the entire world. It was in this context that he traveled to Japan, a country in the midst of reconstruction, still scarred by the aftermath of the war but already eager for modernity.

In Tokyo, Dior was not only received as a designer: he was seen as a symbol of a world reborn, of a refined culture that seemed a million miles away from the deprivations still experienced by the Japanese population. His fashion shows aroused fascination and curiosity. In the newspapers, there was talk of a “clothing revolution,” because Parisian fashion appeared as a new, almost unreal language, contrasting with traditional kimonos or the functional clothes of everyday life.

But the most memorable episode of this trip took place in the classrooms of Bunka Fashion College, the country's most important fashion school. Dior was invited there to meet the students and their professors. The event took on the air of a founding moment: the young designers closely observed the fabrics, the cuts, and the construction of the dresses. Some testimonies say that silence reigned in the workshop, as if each of the couturier's gestures were a revelation. For the first time, the Parisian elite had come to them.

On that day, French haute couture became a teaching tool. Bunka's teachers quickly incorporated the photos and sketches brought back from this historic passage into their classes. Students practiced reproducing the fluidity of Dior dresses with Japanese fabrics, sometimes repurposed: indigo-dyed silks, raw cotton, or fibers from local traditions. From this hybridization emerged the first signs of what would become the strength of Japanese fashion decades later: an ability to absorb Western codes while reinventing them.

Dior, for his part, was impressed by the students' rigor and artisanal precision. In a note written shortly after his trip, he described Tokyo as "a place where couture is a respected art, but still awaiting its own modern language." This sentence sounds like a prophecy: twenty to thirty years later, Bunka would train Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, Kenzo Takada, Junya Watanabe—a generation that would shake up Paris and reverse its outlook.

Dior's visit in 1953 was therefore not just a social event. It marked a cultural turning point: the meeting of two fashion capitals, Paris and Tokyo, which would cease to operate separately from then on. That day, in the Bunka workshops, a lasting bridge was born between East and West, a gateway of inspiration and transmission that still nourishes contemporary creation today.

Yohji and his mother — Sewing as dignity

Yohji Yamamoto was born in 1943, in the midst of World War II. His father died at the front, leaving his mother to raise him alone. A seamstress, she set up her workshop in a small, dark room in Tokyo's working-class Shinjuku district. As a child, Yohji grew up to the sound of scissors and the whir of a sewing machine. In this tiny space, he discovered early on that clothing was not a luxury, but a necessity, a tool for survival and dignity.

His mother worked tirelessly to provide for the household. She made alterations, made kimonos, and adapted worn clothes to give them a second life. Yohji observed this patience and humility. He later said that, in these gestures, he saw an almost sacred act: sewing as a way to protect humanity, to rehabilitate it in the face of life's difficulties.

When he entered Bunka Fashion College in the 1960s, he carried this silent memory within him. Where some students dreamed of the West, the splendor of Paris, or Hollywood catwalks, he chose a different path. His first creations at Bunka were already marked by what would become his vocabulary: loose-fitting, almost masculine garments dominated by black. This black is not an absence of color, but a refuge, an armor, a poetry of shadow.

In 1981, when he presented his first fashion show in Paris, the break was complete. Alongside Rei Kawakubo, he imposed an aesthetic radically opposed to that of European couturiers. The silhouettes seemed deconstructed, the fabrics worn, the shapes asymmetrical. The Western press spoke of “Hiroshima chic,” a clumsy and condescending term that above all revealed the incomprehension of this visual revolution. Yet, behind these dark clothes lies a deeply personal story: a tribute to his mother, to the modest couture that had protected his childhood.

Yamamoto often recounted a striking anecdote: as a teenager, he accompanied his mother to the home of a wealthy client. The latter, with undisguised contempt, treated the seamstress like a servant. For Yohji, this was a revelation: he vowed that sewing would never be reduced to menial labor. In his mind, it should be elevated to the rank of an artistic and social language, capable of defying hierarchies.

All of her work stems from this conviction. Her clothes blur the lines between masculine and feminine, youth and maturity, strength and fragility. They seek not to seduce, but to offer a space of freedom and protection. In each collection, we find the discreet silhouette of this woman who, in a small Tokyo workshop, sewed stubbornly to maintain the dignity of her home.

From the shadows of his maternal atelier to the Parisian catwalks, Yohji Yamamoto transformed couture into a philosophy. His universe, nourished by intimacy and resistance, remains one of the most powerful expressions of contemporary Japanese fashion.