Bunka Fashion College — A Century of Japanese Fashion That Conquered the World

In the heart of Tokyo, in the bustling Shinjuku district, stands an institution that has shaped Japanese fashion and influenced the global scene: Bunka Fashion College. Founded in 1919, this school is much more than an educational institution. It embodies a true cultural laboratory, a place where the greatest Japanese designers were trained, and a mirror of the profound changes in Japanese society. Its history, spanning more than a century, is intimately linked to the evolution of Japanese fashion: from traditional couture inherited from the kimono to the avant-garde daring that shook up Parisian catwalks, to contemporary reflections on sustainability.

Bunka Fashion College doesn't just teach technique. It forges visions. Its students learn to question silhouettes, deconstruct codes, and create a dialogue between heritage and innovation. Many of them— Yohji Yamamoto , Junya Watanabe , Kenzo Takada , Chitose Abe, Nigo, Tao Kurihara, and Noir Kei Ninomiya —have become major figures in international fashion, etching their names into history through radical creations and unprecedented concepts.

This story traces, period by period, the evolution of Japanese school and fashion. We will see how a simple women's sewing school became a global center of creativity, how its graduates imposed a new aesthetic grammar on European catwalks, and how Bunka continues today to anticipate the challenges of tomorrow. Each stage reveals a fertile tension between memory and posterity, technical rigor and creative freedom.

1919 – 1945: Birth of an institution and first foundations

The story of Bunka Fashion College begins in 1919, at the heart of the Taishō era (1912–1926), a pivotal time when Japan was gradually opening up to the modern world. This period was marked by cultural effervescence and a desire to incorporate new inspirations from the West. In major cities like Tokyo and Osaka, a new bourgeoisie emerged: civil servants, prosperous merchants, young women from wealthy families. All aspired to a modern and refined life, influenced by standards from Europe and the United States. In this context, fashion became one of the most visible symbols of this transformation.

It was in this climate that Bunka Fukuso Gakuin ("Bunka Institute of Clothing") was born, the forerunner of Bunka Fashion College. Its initial mission was clear: to offer young Japanese women a modern education, teaching them the basics of sewing and fashion design. The choice to target women was already a revolution. Bunka broke with this logic by placing textile design and the art of clothing at the center of a structured learning process, promoting independence and creativity.

Sewing as a bridge between memory and posterity

In Japan, women's clothing is still largely dominated by the kimono , a symbol of identity and culture par excellence. But in larger cities, more and more women are becoming interested in Western dresses, which are perceived as modern, practical, and socially rewarding. Bunka's role is to teach how to reconcile these two worlds.

Students learn to handle both traditional Japanese fabrics—silk, hemp, cotton dyed using artisanal techniques—and imported fabrics, such as European wool or silk crepe. They are introduced to Western patternmaking , which relies on new cutting techniques different from those used for kimono. These first steps in the hybridization of textile know-how shape the school's DNA: knowing how to draw on heritage while innovating .

At the same time, the school began publishing a pioneering magazine, Bunka Fukuso Zasshi , in the 1920s . Accessible to the general public, this publication popularized Western sewing techniques and disseminated a new aesthetic to a female society eager for change. This magazine became one of the first vectors of modern fashion in Japan. Its influence extended far beyond the school walls and helped establish Bunka as a national authority on clothing education .

Japan in the 1920s: Between Modern Girls and Traditions

In Japanese society in the 1920s, a social phenomenon accompanied this evolution: that of the “moga” (modern girls) . These young urban women, inspired by American flappers and fashionable Parisians, adopted short hairstyles, wore lighter skirts, and frequented the trendy cafés of Ginza. They became the face of a modern, cosmopolitan Japan, sometimes considered scandalous by more conservative generations.

For these young women, learning to make their own clothes was a way to assert themselves. Bunka became one of the places where this emancipation took shape: the school trained not only seamstresses, but also new protagonists of modern Japanese society .

The 1930s: Fashion between modernity and crisis

The following decade, marked by the Shōwa years (1926–1989), saw Japan enter a phase of increasing militarization. But before the war turned everything upside down, Tokyo underwent a period of intense modernization. Department stores like Mitsukoshi and Takashimaya became temples of consumption, displaying Western dresses and modern accessories.

Bunka is fully in line with this dynamic. Students discover the Hollywood silhouettes popularized by actresses like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, but also Parisian elegance, dominated by fashion houses such as Chanel and Vionnet. The school teaches these new codes, while adapting them to the Japanese context: for example, the integration of traditional fabrics into Western cuts.

It was also in the 1930s that Bunka strengthened its teaching methodology by developing the Bunka Fashion Pattern Method , an innovative cutting system that simplified the creation of patterns for Western clothing adapted to Japanese body shapes. This invention, still taught today, is a key milestone in the school's history.

War and Creative Resilience

With the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific (1940–1945), fashion was relegated to the background. Textiles were rationed, colors became more muted, and sewing became primarily utilitarian. Bunka students no longer worked on evening gowns, but on uniforms, functional clothing, pieces designed to last despite the shortages.

Yet this constraint forges a resilience that will profoundly mark the philosophy of the school and its future creators. Learning to create with little , diverting materials from their original use, or sublimating modest fabrics through cutting, becomes a valuable skill. This inventiveness born of restriction will reappear in the 1970s and 1980s with avant-garde creators trained at Bunka, such as Rei Kawakubo or Yohji Yamamoto, who will make black, sobriety and the recycling of materials a true aesthetic.

Legacy of the founding period

Thus, the period 1919–1945 constitutes the intellectual and aesthetic foundations of the Bunka Fashion College. The school develops:

-

a hybrid pedagogy , between traditional kimono and Western fashion,

-

a role of cultural disseminator , via its magazine and its first manuals,

-

a philosophy of resilience , born from the deprivations of war,

-

and above all, a desire to make clothing a tool for individual expression and no longer just a functional or ceremonial element.

By laying these foundations, Bunka established itself in its first decades as the institution that accompanied and shaped Japanese modernity . It prepared, without yet knowing it, the ground for the emergence of designers who would mark the world history of fashion after 1945.

1945 – 1970: Reconstruction, modernization and affirmation of an identity

The surrender of Japan in September 1945 ushered in a new era marked by reconstruction and American occupation. Japanese society was in turmoil: cities were destroyed, the population impoverished, but also unprecedented access to cultural and sartorial influences from the United States. In this context, the Bunka Fashion College played a key role in supporting the country's renaissance through clothing. Fashion became not only an art form, but also a vehicle for dignity and modernity.

Sewing as a symbol of reconstruction

In the immediate postwar period, fabrics were scarce, often from military surplus or recycled clothing. Bunka students learned to transform worn kimonos into Western-style dresses, to improvise cuts with parachute fabrics or discarded uniforms. This constraint forged a pragmatic inventiveness that would become a hallmark of Japanese fashion : the art of innovating with limited resources. This philosophy was later found in the designs of Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, where the initial lack of resources was transformed into a radical aesthetic.

The Westernization of Silhouettes

Under the influence of the American occupation (1945-1952), Japanese women discovered flared skirts, high heels, and Hollywood hairstyles. The Bunka then incorporated Western cutting methods into its teaching. Pattern books were enriched with European and American models, while retaining a Japanese sensitivity to materials and volumes. This hybridization became the school's pedagogical DNA: learning the rules to better break them .

The internationalization of Bunka

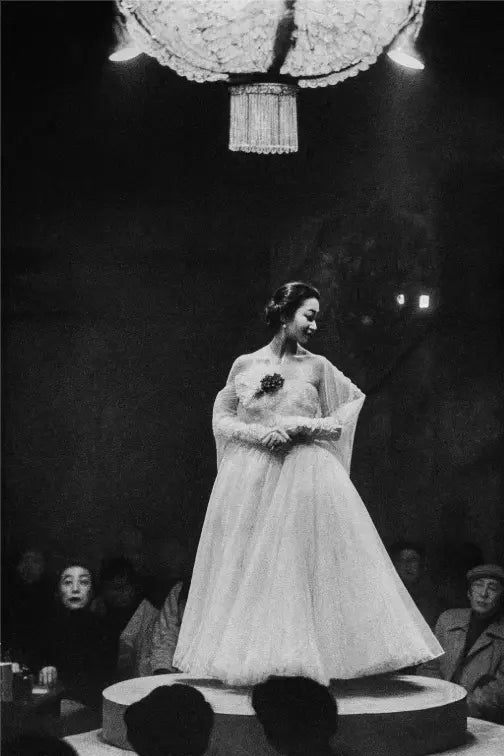

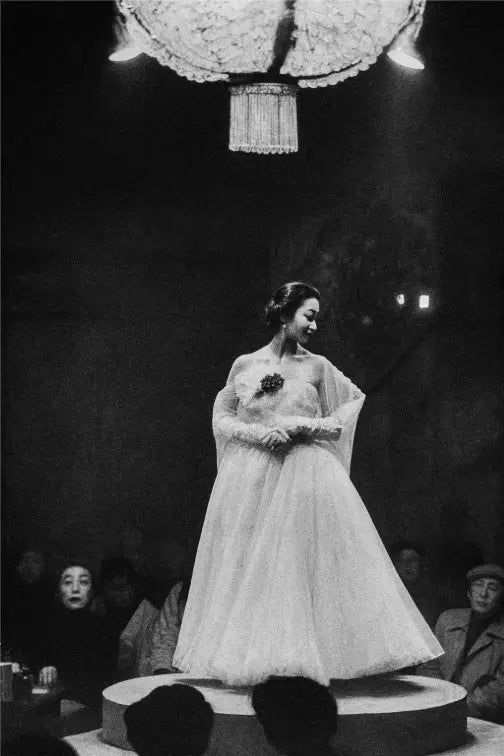

From the 1950s onwards, Bunka affirmed its desire to become an institution of international influence. The school established an exchange program and attracted its first foreign professors. At the same time, it trained a new generation of designers ready to transcend borders. The highlight of this decade remains the arrival of Christian Dior in Tokyo in 1953 , who organized a fashion show at Bunka. This moment symbolized Japan's official entry into the international fashion scene. The students discovered firsthand the elegance of the New Look and understood that haute couture could be a universal language.

The first creators to establish themselves

It was during this period that Bunka began training those who would become pioneers. Among them, Kenzo Takada , who arrived in Paris in 1964, is a symbol: a Bunka graduate, he chose the French capital as a springboard and founded his house in 1970. His career illustrates the school's strategic role: providing solid technical mastery and a cultural openness that allows Japanese designers to compete with the best on the world stage.

The 1960s: Birth of the Avant-Garde

The 1960s were marked by cultural effervescence and the rise of a rebellious youth. Japan experienced its "economic miracle," and consumer society took hold. Fashion became a platform for expressing this modernity. Bunka supported this movement: its students experimented with new cuts, drawing inspiration from Pop Art, French cinema, and rock music. The school then created an avant-garde incubator , where the aesthetic revolution that would erupt in the 1980s was already being prepared.

At the same time, Japanese designers were beginning to gain international attention. While the Japanese textile industry remained dominated by mass production, Bunka established itself as a hotbed of creative singularity , attracting the attention of European fashion critics and editors.

Bunka, a unique pedagogy

What distinguished Bunka from other fashion schools at the same time was the combination of three approaches:

-

Technical rigor : in-depth learning of cutting, molding and sewing, with a precision inherited from Japanese craftsmanship.

-

An international outlook : integration of Western trends, participation in global competitions, and encouragement of careers outside Japan.

-

An experimental culture : the school allows students to challenge the rules, test new materials, and repurpose industrial textiles.

This pedagogy creates a pool of free spirits, capable of transforming constraints into aesthetics and elevating Japanese fashion to the rank of recognized art.

Period conclusion

Between 1945 and 1970, Bunka Fashion College grew from a national fashion school to a global platform for creativity . In the midst of the country's reconstruction, it forged the first generations of designers capable of engaging with the West, while preparing the avant-garde explosion of the following decades.

1970–1989 — Japanese avant-garde conquers the world

The 1970s and 1980s marked a major shift in the history of global fashion. After long being confined to the role of observer or discreet inspiration, Japanese fashion took center stage, shaking up Paris, the capital of luxury and ready-to-wear. This radical change owed much to the Bunka Fashion College , a veritable breeding ground for talent, and to a generation of visionary designers who, trained in its workshops, would export a singular, sometimes disconcerting, but always revolutionary aesthetic internationally. This was the era of conquest: Kenzo Takada, Yohji Yamamoto, Rei Kawakubo , soon followed by Junya Watanabe, Michiko Koshino and others, transformed the perception of Japanese fashion and opened a new era: that of the Japanese avant-garde.

Kenzo Takada, the flamboyant scout

The 1970s began with Kenzo Takada , the first major Japanese fashion ambassador in Europe. A Bunka graduate, he left Tokyo in the late 1960s to settle in Paris, where he opened his first boutique, "Jungle Jap," in 1970, decorated with colorful frescoes by his painter friend. His fashion shows, held under marquees or in unexpected locations, made an impression with their energy, inventiveness, and joie de vivre. Kenzo blended Asian, African, and Western references in an explosion of colors and floral prints. He proved that Japanese fashion was not limited to austerity or minimalism and quickly won over an international audience. His festive approach contrasted with what his compatriots would offer in the following decade, but it laid the foundations: a Japan capable of asserting itself in Paris by embracing its difference.

The 1980s: The Yamamoto-Kawakubo clash

The year 1981 was a turning point. During Paris Fashion Week , two Japanese designers caused what the press called an "aesthetic earthquake": Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo .

-

Yohji, a 1969 Bunka graduate, arrives with black, loose, unstructured silhouettes that abolish the codes of Parisian couture. Clothing is no longer a tool of seduction but a poetic armor, where imperfection becomes beauty.

-

Rei Kawakubo, founder of Comme des Garçons , introduces a new radicalism: brutal asymmetries, distorted volumes, frayed fabrics. The French press speaks of "Hiroshima chic," shocked by this dark and disturbing aesthetic.

What was seen as a provocation turned out to be a revolution . Black, until then associated with mourning in the West, became the queen color of modernity. The codes of clothing—cut, proportion, function—were challenged. The public discovered a different way of thinking about fashion: not as a simple dressing of the body, but as an artistic language capable of questioning society.

Bunka, matrix of the avant-garde

If Yamamoto and Kawakubo became icons of this decade, their success was also that of Bunka Fashion College . The school, from the 1970s, strengthened its international role by opening its doors to foreign students and increasing academic exchanges. In Tokyo, its campus now attracts as much for its technical rigor as for its cultural openness. The construction of a new skyscraper in 1979 , in the Shinjuku district, embodies this ambition: modern workshops, specialized library, textile research spaces. The establishment gives itself the means to compete with Central Saint Martins in London or Parsons in New York , and becomes the essential Asian reference for anyone wishing to pursue a career in fashion.

Iconic figures of the 1980s

The Japanese avant-garde was not limited to Yamamoto and Kawakubo. Several Bunka designers imposed their style in these two decades:

-

Hiroko Koshino , who combines Western elegance with Asian touches, has shown many shows between Paris and Tokyo.

-

Junko Koshino , whose revisited kimonos are entering the collections of international museums.

-

Michiko Koshino , based in London, who became a pioneer of streetwear and dressed the British clubbing scene.

-

Junya Watanabe , trained at Comme des Garçons after graduating from Bunka in 1984, began his rise with his technical experiments and patchworks.

These names draw a constellation of styles, but all share the same DNA: audacity, technical rigor and a desire to shake up the norms.

A fashion in tune with its times

This triumph of the Japanese avant-garde took place in a particular context. The 1980s corresponded to Japan's period of high economic growth . Tokyo became a world capital, bubbling with creative energy, where new subcultures emerged: Japanese punk, Harajuku underground fashions, and the explosion of streetwear. The designers trained at Bunka thrived on this effervescent environment. They translated the paradoxes of contemporary Japan into their clothes: technological modernity and artisanal tradition, economic optimism and the painful memory of the post-war period. This tension between past and future gave rise to unclassifiable pieces that fascinate as much as they disturb.

Parades as manifestos

Kawakubo and Yamamoto's shows in the 1980s weren't just collection presentations: they were true aesthetic manifestos . Kawakubo shocked the public by presenting ripped silhouettes in 1982 that challenged the idea of luxury and beauty. Yamamoto, for his part, elevated black, declaring in an interview with Spectr magazine: "Black is both modest and arrogant. Black is lazy and easy—but mysterious." These words reflected the philosophy of an entire generation: rejecting easy seduction and questioning the very meaning of clothing.

The central role of Paris

Paris remained the main arena for international recognition at this time. While Bunka trained talent, it was in Paris that it truly revealed itself. The French capital, despite its initial resistance, eventually embraced Japanese designers, fascinated by their audacity. In 1982, Le Monde magazine headlined: "The Japanese Invent a New Fashion." From then on, the Japanese avant-garde became a category in its own right in the fashion show calendar. The link between Tokyo and Paris was consolidated, and Bunka became the obligatory stopover for all eyes on Japan.

Conclusion: a founding golden age

The period 1970–1989 definitively established Japan's role in global fashion. Thanks to Bunka Fashion College , Japanese designers went from outsiders to respected pioneers. Kenzo Takada led the way, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo imposed their radicalism, while others like Michiko Koshino and Junya Watanabe were already preparing the next generation. This generation changed the perception of fashion: it could be dark, conceptual, and anti-establishment, but also profoundly poetic. The history of Bunka is inseparable from this conquest, because without its demanding teaching and international vision, this effervescence would not have had the same scale. It was a golden age, a founding moment that etched a certainty in the collective imagination: the future of fashion was also being played out in Tokyo .

1990–2000 — The new generation and the advent of Japanese streetwear

The 1990s opened a decisive chapter in the history of Japanese fashion and Bunka Fashion College . After the aesthetic shock of the 1980s led by Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo , the following decade saw two parallel dynamics emerge: on the one hand, the consolidation of a conceptual avant-garde now established in the Parisian calendar, and on the other, the emergence of a Japanese streetwear culture that would conquer the world's youth. Bunka, always at the center, trained a new generation of designers capable of dialoguing with this heritage while opening up new perspectives. It was the decade of hybrid experiments , where luxury, urban culture and Japanese traditions intertwined.

A context of economic and cultural change

Japan in the 1990s was marked by the bursting of the speculative bubble and the entry into what is known as the "lost decade." Economic growth was slowing, but paradoxically, the cultural and creative scene was exploding. Tokyo, and in particular the Harajuku district , became a laboratory for stylistic experimentation. Young people appropriated fashion as a language of identity, while the street inspired professional designers. This effervescence also fueled the Bunka, which saw an influx of a generation of students fascinated as much by the legacy of Yamamoto and Kawakubo as by new urban energies.

The consolidation of the masters of the avant-garde

In the 1990s, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo continued to dominate the international scene. Yamamoto collaborated with Adidas to create Y-3 (2000, officially released a little later), foreshadowing the alliance between sport and haute couture. Rei Kawakubo, meanwhile, multiplied the lines derived from Comme des Garçons (Homme Plus, Shirt, Tricot, Play, etc.), asserting a strategy of global expansion without ever denying her creative radicalism. These two figures remain the absolute reference for Bunka students, proof that the avant-garde has not said its last word.

Junya Watanabe, the experimental heir

Among Bunka alumni, Junya Watanabe embodies the next generation of the 1990s. Assistant to Rei Kawakubo upon leaving school, he launched his own line in 1992 under the aegis of Comme des Garçons. Known for his work with technical materials, patchwork, and deconstruction , Watanabe perfectly exemplifies the Bunka philosophy: technical rigor and conceptual audacity. His collections of the 1990s, often praised for their inventiveness, reinforced Japan's reputation as a land of innovation.

The emergence of Japanese streetwear

While the avant-garde remained influential, the great revolution of the 1990s was elsewhere: it came from the streets. Tokyo became the capital of sophisticated streetwear that fused hip-hop, skate, punk, and Japanese influences. Three figures dominated this scene, all directly or indirectly linked to Bunka and Harajuku:

-

Hiroshi Fujiwara , pioneer of the Ura-Harajuku movement, DJ and stylist, considered the “godfather of Japanese streetwear”.

-

Nigo (Tomoaki Nagao) , a Bunka graduate, founded A Bathing Ape (BAPE) in 1993. His camouflage patterns, full-zip hoodies, and exclusive sneakers created a real craze in Japan, before seducing American rappers like Pharrell Williams and Kanye West.

-

Jun Takahashi , also from Bunka, launched Undercover in 1993. Inspired by British punk and underground culture, he offers a dark, conceptual wardrobe but anchored in the street.

These brands mark the birth of high-end streetwear ahead of its time, twenty years before the phenomenon exploded in Europe and the United States. They rely on quality local production, faithful to Japanese textile excellence, and on an aesthetic that combines humor, social critique, and sophistication.

Bunka, hybrid crop incubator

In the 1990s, Bunka Fashion College was no longer just a place for technical transmission: it was an incubator for subcultures . The school now welcomed students who wanted not only to enter Parisian haute couture but also to invent a sartorial language rooted in the street. The proximity to Harajuku, the temple of urban style, encouraged this osmosis. The end-of-year fashion shows became events followed by the international press, as they revealed the trends that would dominate the following decade.

Harajuku and the Visual Revolution

It's impossible to talk about this period without mentioning the role of Harajuku . A true urban theater, this Tokyo district is the laboratory where the most radical styles were born: Gothic Lolita, Visual Kei, Gyaru, but also the Ura-Hara style that would give birth to global streetwear. Photographer Shoichi Aoki, with his magazine FRUiTS (launched in 1997), immortalized these extravagant looks and helped to make this creativity known internationally. The designers from Bunka tapped into this excitement, while directing it towards structured collections that appealed to Western buyers.

International recognition of Japanese streetwear

The late 1990s saw the global success of Japanese streetwear. BAPE pieces were sold out in limited editions, Undercover's collections were presented in Paris as early as 2002 but were already resonating strongly in the 1990s, and Hiroshi Fujiwara multiplied his collaborations with Nike, Levi's, and Stüssy. This recognition transformed Japan's image: it was no longer just the cradle of the conceptual avant-garde, but also that of a young, influential urban fashion.

Tradition and modernity: a Japanese constant

Despite the rise of streetwear, the decade didn't turn its back on Japanese traditions. Several designers continued to explore kimonos, indigo, artisanal weaving, and silhouettes inspired by Japanese history. Junya Watanabe, for example, regularly reinterprets classic Japanese cuts by hybridizing them with technological materials. This tension between heritage and futurism remains the signature of Bunka and its graduates.

Towards a globalization of Japanese fashion

The 1990s laid the foundations for the accelerated globalization of Japanese fashion. For the first time, brands born in Tokyo became global phenomena . Bunka, already recognized as one of the world's leading fashion institutes, saw its prestige strengthened. Young designers knew they could now conquer Paris, New York, or London, as well as influence global urban cultures. This decade thus paved the way for the explosion of the 2000s, when Japanese fashion became essential in all its forms: avant-garde, luxury, streetwear, and international collaborations.

Conclusion: The Decade of Crossbreeding

Between 1990 and 2000, Japanese fashion underwent a profound transformation. The masters of the avant-garde consolidated their status, but a new generation trained at Bunka opened up new horizons. Junya Watanabe embodied radical experimentation, while Nigo and Jun Takahashi imposed a sophisticated streetwear that redefining global urban culture. Harajuku became the visual symbol of this effervescence, and Tokyo definitively asserted itself as one of the world's fashion capitals. This decade of crossovers and hybridizations confirmed one obvious fact: Japanese fashion was no longer a periphery but a center , capable of inspiring Parisian catwalks as much as the streets of New York or London.

2000 – Today: Bunka in the global era, laboratory of contemporary fashion

A strategic turning point for Bunka

At the dawn of the 2000s, Bunka Fashion College entered a new phase in its history. Having shaped the Japanese avant-garde of previous decades, the school faced an unprecedented challenge: how to maintain its global aura in an era where fashion was simultaneously globalized, digitalized, and fragmented ? Bunka's answer was clear: establish itself as a laboratory of innovation where tradition and the future collide.

Japan, already renowned for the quality of its craftsmanship and the radicalism of its creators, became a center of international attraction with Bunka. The school then developed a three-pronged strategy:

-

Internationalization of courses : opening programs in English to attract foreign talent.

-

Technologies and digital : integration of 3D software, digital printing and new prototyping practices.

-

Sustainability and ethics : gradual introduction of modules on textile recycling, upcycling and social responsibility, anticipating concerns that will dominate the years 2010-2020.

The 2000s: the emergence of a new generation

In the 2000s, Bunka continued to fuel the global industry with creators from its pool.

-

Chitose Abe , who worked for Bunka and then Comme des Garçons, founded Sacai in 1999 , a brand that would become emblematic of the 2000s and 2010s with its hybrid style, combining sportswear, luxury and Japanese tailoring.

-

Tao Kurihara , also trained at Bunka and close to Rei Kawakubo, imposes a poetic and unstructured vision, in the continuity of the avant-garde spirit.

-

Junya Watanabe , already active since the 1990s, has established himself as one of the most influential creators of the 2000s thanks to his high-tech experiments and his visionary relationship with materials.

This generation embodies the diversity of voices formed by Bunka : some in the tradition of radical anti-fashion, others exploring the fusion of genres, and still others seeking to integrate Japanese fashion into the global luxury system.

The 2010s: Bunka and the Digital Age

With the advent of social media and digital commerce, fashion is entering a new era. Instagram, TikTok, and resale platforms are revolutionizing our relationship with clothing. Bunka, true to her pioneering role, is adapting her teachings:

-

setting up digital studios to train students in virtual design and online presentations,

-

collaboration with Japanese technology brands (such as Sony or Epson) on connected clothing projects,

-

creation of modules dedicated to personal branding and digital communication, in order to help young creators exist in a world saturated with images.

Bunka's graduate shows then become true media events, followed via streaming by an international audience. They constitute a laboratory of ideas where tomorrow's trends are tested, often before arriving on Western catwalks.

Focus on sustainability: a new philosophy

During the years 2010-2020, in the face of criticism of the fashion industry for its environmental impact, Bunka introduced teaching focused on sustainability .

-

Development of courses around upcycling , with workshops where students rework vintage clothing.

-

Studies on innovative Japanese fibers: organic cotton from Okinawa, revisited silk, high-performance recycled polyester.

-

Partnerships with committed companies to link textile research and ecological awareness.

This direction responds to the rise of a generation sensitive to ethics and places Bunka as a precursor of responsible fashion .

The 2020s: Bunka in the Post-COVID Age of Global Creativity

The 2020 health crisis accelerated digital transformation. Bunka students presented their collections on virtual platforms, sometimes incorporating augmented reality and NFTs into their projects. This period confirmed the school's ability to reinvent presentation formats and stay in step with industry changes.

At the same time, Bunka is consolidating its role as an international crossroads:

-

Students from more than 50 countries now attend his classes.

-

The school is increasing its collaborations with Paris, London and New York , but also with Seoul and Shanghai, affirming its central role in Asia.

-

The workshops integrate issues of cultural diversity : Bunka no longer teaches only “Japanese fashion”, but a vision where each identity can find its place.

Bunka, a brand in itself

Today, the name Bunka Fashion College has almost become a global brand . For fashion enthusiasts, joining Bunka means joining a prestigious lineage:

-

Rei Kawakubo : the art of deconstructing the silhouette.

-

Yohji Yamamoto : the poet of darkness and breadth.

-

Kenzo Takada : the explosion of color and mixing.

-

Junya Watanabe : The Visionary Textile Engineer

-

Chitose Abe : The Magician of Hybridizations.

These figures embody the diversity of possible paths after Bunka, but all demonstrate the same requirement: technical rigor, creative freedom, and a desire to challenge the norms .

Conclusion: Bunka, a future still under construction

From 2000 to today, Bunka Fashion College has remained at the center of global fashion by combining heritage and innovation. As contemporary fashion questions its role in a world in ecological crisis, digital transformation and in search of meaning, Bunka positions itself as a laboratory school , faithful to its mission: to train designers capable of thinking of fashion as a universal language .

In 2025, Bunka celebrates more than a century of existence. But its spirit remains resolutely young, driven by the conviction that fashion is not just a matter of trends, but a cultural, social, and political tool . The designers who will graduate from its classes tomorrow will extend this adventure, inscribing their names alongside their illustrious predecessors.

Tracing the history of Bunka Fashion College since 1919, it becomes clear that this school is not just an academic institution, but a true matrix of Japanese fashion . Each period, from the modernization of pre-war Japan to the digital and ecological upheavals of our time, has seen Bunka reinvent itself to train designers capable of translating their time into clothing.

From the post-war period , when the school laid the foundations for an autonomous Japanese identity, to the 1970s and 1990s , a golden age when Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto and Kenzo Takada shook up the codes in Paris, Bunka was the matrix of international recognition for Japanese fashion. Then, from the 2000s onwards, with Junya Watanabe, Chitose Abe (Sacai) and Tao Kurihara, the school demonstrated its ability to produce talent in line with the challenges of global luxury, digital technology and sustainability.

Today, Bunka positions itself as a global laboratory where Japanese textile tradition and technological innovations meet. Its workshops train designers who no longer see fashion as a simple product, but as a universal language capable of expressing individuality, collective memory, and societal concerns.

Bunka's true strength is that it has never given in to nostalgia. It continues to move forward, faithful to a simple idea: fashion is a living art, and each generation must invent its own aesthetic.

Thus, from Tokyo to Paris, from New York to Seoul, the name Bunka resonates as a pledge of excellence, creativity, and avant-garde. Bunka's story is not over: it is being written, in the hands of its students, future heirs and builders of tomorrow's fashion.